Transforming policy and practice in palliative and end-of-life care of people with intellectual disabilities

Making life's end easier for those with intellectual disabilities

People with intellectual disabilities account for 2% of the total UK population. They often face significant under-recognised needs for end-of-life care. Moreover, they experience profound healthcare inequalities and lack access to palliative care services, a situation that has only worsened during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Professor Irene Tuffrey-Wijne of Kingston's Centre for Health and Social Care Research has contributed to fulfilling the unmet needs of this population through her pioneering research on end-of-life care, grief and communication about death. Her work has established that social and health care staff often have limited knowledge on how to support people with intellectual disabilities in cases of bereavement or end-of life-decisions. This gap can lead to people with intellectual disabilities being excluded from education on death and making it harder for them to deal with grieving, as well as increasing stress on staff.

Influencing national and international policy

Professor Tuffrey-Wijne's work has influenced national and international policy through health departments and organisations, improved staff training in the UK and internationally, and increased professional understanding of end-of-life care for people with intellectual disabilities. Starting in 2012, she worked with the European Association of Palliative Care to set international standards for end-of-life care for people with intellectual disabilities.

She set up and led a committee of 12 experts in the field from seven EU countries to develop consensus on palliative care for this population (irrespective of their social, national or cultural background), identify best practices and draft norms. The committee's work generated significant insights: people with intellectual disabilities do not have equal access to palliative care; many needs of people with intellectual disabilities are misunderstood or unmet; and good practice depends on the commitment of dedicated individuals rather than on good policies, systems or guidelines.

Professor Tuffrey-Wijne's work has generated and influenced changes in national and international end-of-life policies. In the UK, her work led to the publication of the NHS England's guidelines Delivering High Quality End of Life Care for People who Have a Learning Disability (2017). In the Netherlands, the Dutch Society of Physicians for Persons with Intellectual Disabilities started a project on implementing EU end-of-life norms. In Victoria, Australia, her research helped implement the public health approach to end-of-life care of people with intellectual disabilities.

Changing professional practice

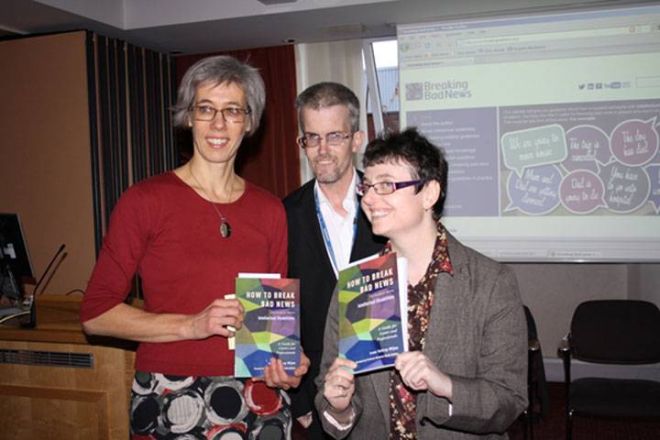

Professor Tuffrey-Wijne's work has also changed professional practice. Two UK intellectual disability service providers have based their end-of-life care policies and support materials on her research, and a US company has worked with her to develop online training materials for intellectual disability staff worldwide.

She has disseminated her findings in different formats, including books and materials in lay language, as well as picture books. One such resource, titled Jenny's Diary and available in six languages, helps people with intellectual disabilities and dementia to understand their own illness.

Professor Tuffrey-Wijne's studies and resources have helped make the inevitable process of dying and bereavement easier for people with intellectual disabilities and have led to increased awareness among staff, carers, managers and policymakers.

Contact us

- For non-student research enquiries, email the Research Office

- For research impact and REF enquiries, email the REF and Impact Team.

- Research contacts

- How to get to Kingston University