Unearthing the hidden women of science and inspiring the next generation

Posted Wednesday 8 May 2013

A group of historians and scientists is about to embark on a major project to scrutinise the role of British women in science. They will focus on finding and assessing the careers of scientific women who may not have received credit or recognition for their work. The £33k project, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and run jointly by Kingston University, University of Liverpool, the Royal Society and the Rothschild Archive London, aims to examine how women were involved in scientific societies between the years 1830 to 2012 and look at how that can inform policy today.

A group of historians and scientists is about to embark on a major project to scrutinise the role of British women in science. They will focus on finding and assessing the careers of scientific women who may not have received credit or recognition for their work. The £33k project, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and run jointly by Kingston University, University of Liverpool, the Royal Society and the Rothschild Archive London, aims to examine how women were involved in scientific societies between the years 1830 to 2012 and look at how that can inform policy today.

It will involve the establishment of a network of academics to gain a better understanding of how historical perspectives might impact future education policy making. Recent statistics show that only a third of science, technology, engineering and maths students in Britain are female and just 11 per cent of senior positions in science are held by women.

"Women's unequal participation in science subjects at all levels, both in education, academia and in industry, is currently receiving close attention from policy makers, educationalists and social commentators," project leader Dr Susan Hawkins, a senior history lecturer from Kingston University, said. "Part of the purpose of our work will be to closely examine data on women in science in the 19th and 20th Centuries. The hope is that by looking at women's relationship with science in the past, we can pinpoint ways to encourage young women to participate more fully in the subject."

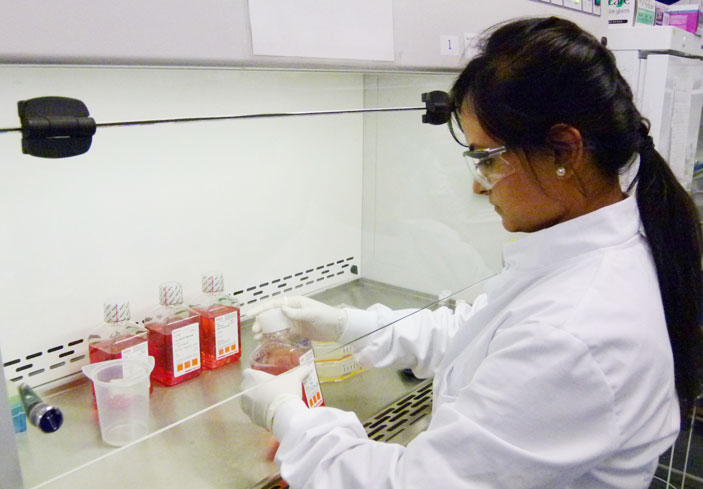

There was a wealth of historical information which could open a window into the past but it was often dispersed across different archives, Dr Hawkins, who originally trained as a scientist, explained. "Through the network we hope to identify where these archives are and what revelatory material they may contain." Part of the project will involve a shadowing scheme which will allow researchers studying the history of science to spend time alongside a female scientist in the laboratory, gaining an understanding of how science works today and the challenges faced by women in the field.

The network will be organised around a series of events, including three workshops, a two-day international conference to be held at the Royal Society in May 2014 and an exhibition open to the public. The first workshop will aim to identify archives that may contain information on women in science. It will concentrate on two groups of women - those whose work was recognised by the scientific community of their time and those who, despite producing work of high standard, were not. "The intention is to look at the characteristics that link the two groups of women and also to find out what set them apart," Dr Hawkins added. Another workshop will focus on identifying possible oral history projects.

The network will be organised around a series of events, including three workshops, a two-day international conference to be held at the Royal Society in May 2014 and an exhibition open to the public. The first workshop will aim to identify archives that may contain information on women in science. It will concentrate on two groups of women - those whose work was recognised by the scientific community of their time and those who, despite producing work of high standard, were not. "The intention is to look at the characteristics that link the two groups of women and also to find out what set them apart," Dr Hawkins added. Another workshop will focus on identifying possible oral history projects.

"The final workshop will pull together the findings from the first two events and allow us to make recommendations to government on future projects to help increase female participation in science," Dr Hawkins said.

The issue of the representation of women in science has dominated headlines in the media in recent months. According to a report in last month's Independent newspaper, female professors account for 5.5 per cent in physics, 6 per cent in chemistry and maths and just 2 per cent in engineering. This has prompted growing calls for better representation of women in science both in universities and in industry - a sentiment also echoed by Kingston University's new Chancellor American playwright and author Bonnie Greer. "It is crucial that women continue to take up the study of science and maths as historically women have been kept out of these professions, so who knows what genius has been lost?" she said recently. "When you think of all the big problems that are out there waiting to be solved, every ounce of human intelligence is needed."

Things were extremely tough for women in science in the past and they often did not receive proper recognition, according to Dr Hawkins. "It was a real struggle. For instance, the Royal Society didn't accept female fellows until as late as 1945," she said. "There were women in the scientific field but they really had to fight to be recognised, independent of any men they might have been working with."

Guests from around the world will attend a launch event for the project at the International Congress for the History of Science Technology and Medicine to be held in Manchester in July.

- Find out more about the Women In Science project.

- Find out more about studying undergraduate and postgraduate science at Kingston University.

Contact us

General enquiries:

Journalists only:

- Communications team

Tel: +44 (0)20 8417 3034

Email us