How Black History Month has inspired research into the stories and achievements of Black figures from Kingston and Surrey's past

Posted Monday 5 October 2020

Kingston University historian Dr Steven Woodbridge explores how recent research inspired by Black History Month is shining a light on the Black history of Kingston and its surrounding areas.

Although Black people have lived in this country since Roman times, members of Britain's Black community were first recorded officially in the Tudor period - and one talented Black musician was a regular presence just down the road at Hampton Court Palace, during the reign of King Henry VIII. Paintings from the time show that John Blanke was a Black trumpeter, one of the six elite trumpeters in the Royal retinue to the King (the other five were white). Blanke was clearly well-regarded by Henry, as he successfully petitioned the King for a wage increase.

This is just one of the fascinating pieces of new local research that has emerged in recent years as a result of exciting initiatives taken by scholars who have been inspired by Black History Month. Black History Month is a month of events in October which takes place annually and celebrates the culture, history and achievements of Britain's African, Caribbean and Asian communities, including locally in south-west London.

Although the event had its origins in the United States, the British version has become more and more attuned to what is distinctive and vibrant about Black history in this country. Black History Month has taken place every October since 1987 and, importantly, helps us to understand and appreciate the extent to which the United Kingdom has had a very long history of migration and contributions from people with African and Caribbean heritage, together with those of Asian ancestry. Britain, and London especially, enjoys a rich and diverse Black and Asian cultural and historical legacy, something that for a long time was hidden from mainstream public debate, and also - tragically - from many history textbooks and curricula. Black History Month has helped historians address this problem and restore Black Britons to their rightful place in our national story.

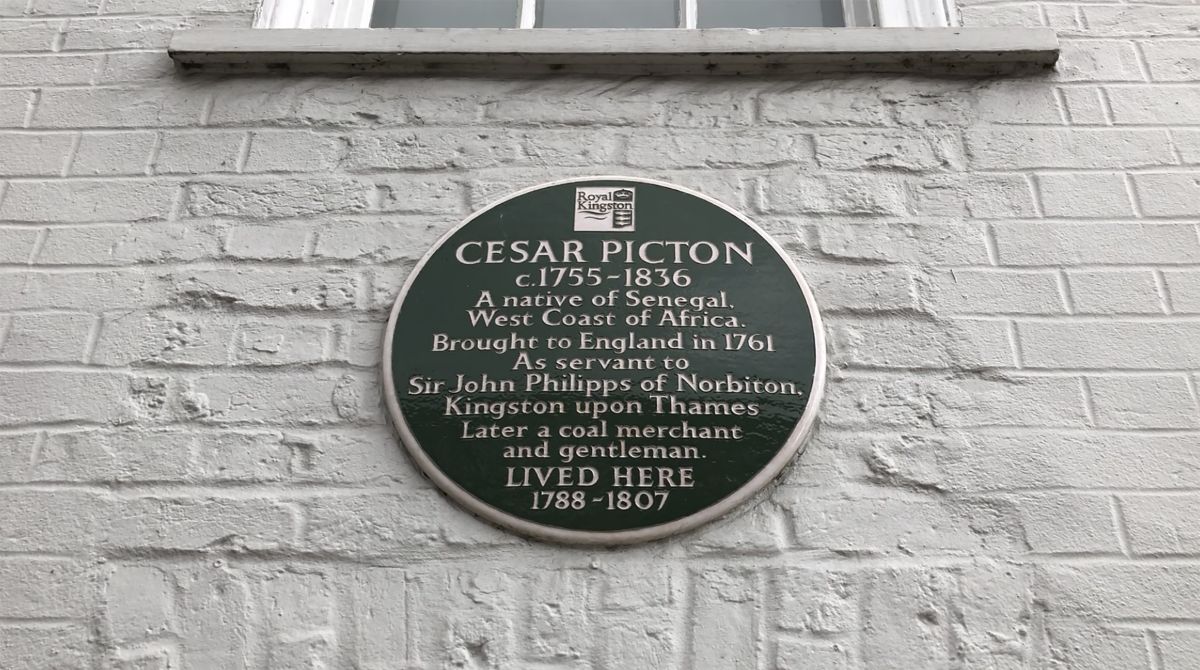

New historical research at local level illustrates this perfectly, and interest in the history of slavery is a case in point. More people are now aware, for example, of the life of former slave Cesar Picton, who was brought to England from Senegal as a gift for a local family in 1761. He went on to become a coal merchant and a wealthy and respected gentleman, and he remains Kingston's most famous eighteenth century Black businessman. His former homes in Kingston and Thames Ditton are marked by commemorative plaques. He has also been commemorated at Kingston University's main campus through the Picton Room, which was named after him.

Recent research has also brought to light some fascinating details about another African slave, Charlotte Howe, who was brought to Britain from America in 1781 by Captain Howe, and ended up residing in Thames Ditton as a servant to Howe. After her master's death, there was quite a legal debate about whether her status in Britain remained one of slave, the same as she had been in America.

In fact, significant evidence has been discovered recently about the County of Surrey's troubled relationship with slavery. It has been estimated that, in 1830, the County still had about 100 slave owners, and in September of this year a survey by the National Trust revealed how some of its properties had originally been financed in part from the vast fortunes made from slavery and British colonialism, including Ham House (between Kingston and Richmond) and Clandon Park House, near Guildford.

Some ground-breaking evidence has also emerged from the early twentieth century about local Black and Asian roles in the politics of the Thames Valley area. In 1922, Shapurji Saklatvala, who was of Indian Parsi heritage, became the third ethnic Indian elected to Parliament, and was a controversial but very popular Communist MP for North Battersea in the 1920s. He used to reside in Twickenham and, as a former member of Twickenham Labour Party, was a regular ‘celebrity' visitor to the local area, delivering numerous ‘seditious' speeches on politics to packed meetings, much to the alarm of the local authorities.

The invaluable role of members of the Black community in the more recent social life of the Kingston area is also something that historians are now more aware of thanks to Black History Month. My own research on patterns of immigration in the post-1945 period, and how this impacted on the Thames Valley, has pointed to some further instances of black individuals from all walks of life who, in their own quiet but very important ways, became essential parts of the local community.

A great example was ‘Ollie' Johnson, who came to Britain as part of the Windrush generation in the late 1950s (so named after the Empire Windrush, the ship that brought one of the first groups of West Indian migrants to Britain in 1948). Ollie settled in Wimbledon and initially worked as a municipal refuse collector, but from the 1960s until his retirement in the 1990s he was a dedicated and hardworking gravedigger at Surbiton cemetery in Lower Marsh Lane, building up his savings and waiting for the day he could retire back to his plot of land in Jamaica.

During the course of his long local career, Ollie helped bury many hundreds of deceased Kingston and Surbiton residents and was a very popular character in the local area, especially admired for his gardening knowledge and skills, which he would happily share with residents, and for his cheerful early morning greetings to students over the railings at the nearby Clayhill residence.

As a number of commentators have aptly pointed out, perhaps one day there will cease to be a need for Black History Month, when Black history is universally accepted as British history and is studied and celebrated all year long around the country. Until then, however, Black History Month remains vital in helping us understand more accurately the historical origins and makeup of British identity today.

Dr Steven Woodbridge is a senior lecturer in history in the School of Arts, Culture and Communications at Kingston School of Art.

- Find out more about how Kingston University is marking Black History Month.